Another milestone along that interminable trip from London to Scotland when Daryl and I unwittingly laid Thinking 3D’s foundations (see last week’s entry for the Book of the Week), was the work on perspective by the Venetian Patrician Daniele Barbaro (1514-70).

On that train, we were bringing with us a metaphorical suitcase containing almost four years of reseach and collaborative work on Barbaro’s manuscripts and printed books – made possible thanks to grants from The Delmas Foundation, the British Academy, the Carnegie Trust, and above all the Leverhulme Trust –, and the enthusiasm for a then ongoing exhibition entirely dedicated to him at the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana in Venice, where the majority of his writings are preserved nowadays.

Barbaro was a leading figure in the cultural life of his time. An eminent humanist with encyclopaedic interests, he published several books and left unpublished writings on a formidable range of subjects. The corpus of his writings reflects the multifaceted nature of his personality and the broad spectrum of his interests and activities. Best known as the editor of three editions of Vitruvius’ De architectura illustrated by Andrea Palladio (1556 and 1567, in Italian and Latin), his books also include Exquisitae in Porphirium commentationes (1542); Predica dei sogni (1542); Rhetoricorum Aristotelis libri tres (1544); Della eloquenza (1557); La pratica della perspettiva (1568); and Aurea in quinquaginta (1569) (you can see the full catalogue, with abundance of additional information here).

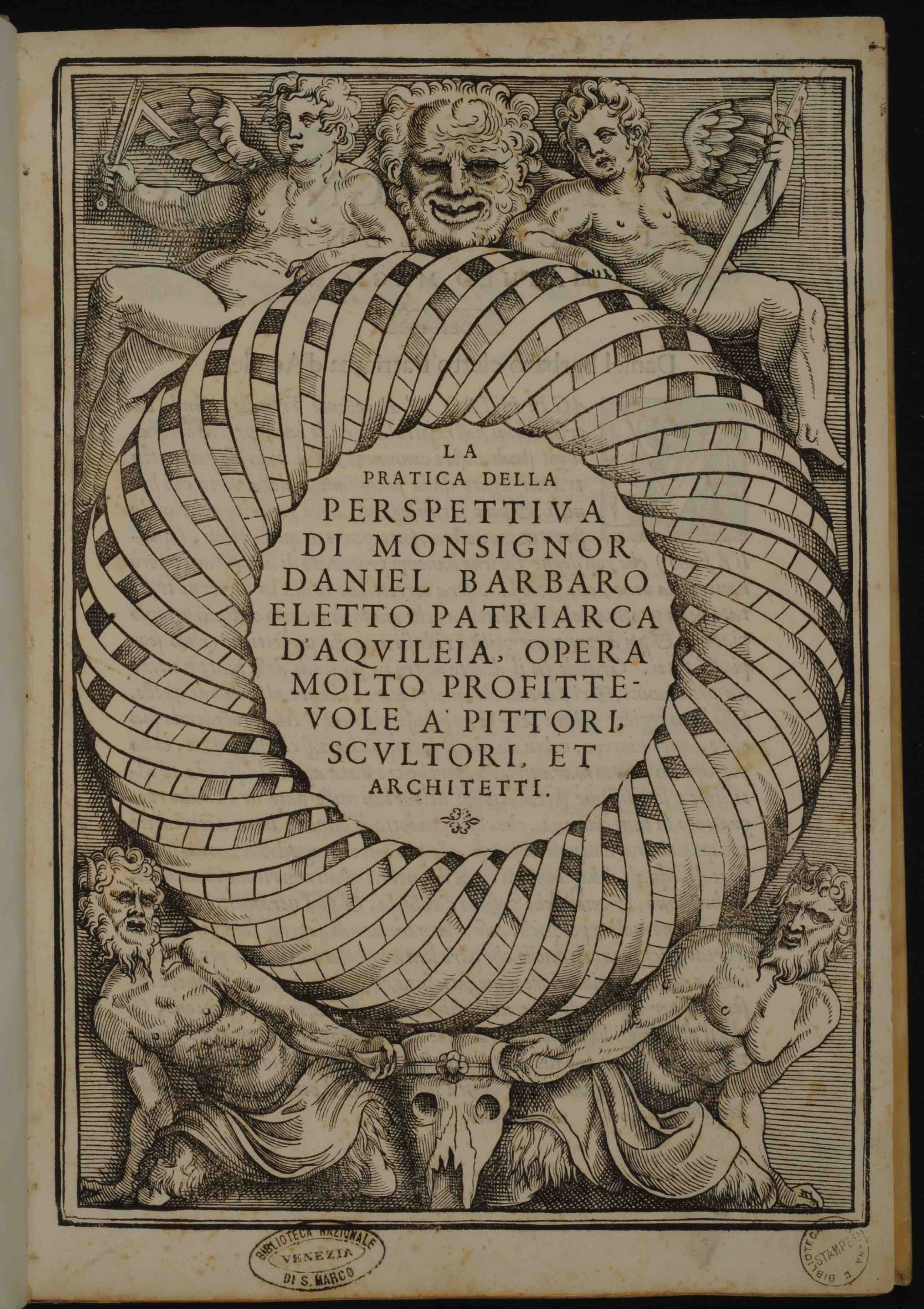

In 1568, the Venetian printers Camillo and Rutilio Borgominieri published La pratica della perspettiva, one of Barbaro’s most interesting and controversial works. The book was reprinted and reissued with minor variations at least 5 times in a timespan of 2 years. The intention of the author was to offer a practical manual to painters, sculptors and architects on the rules of perspective. As Barbaro observes in the Proemio, although these rules were largely employed by artists since anquity, none ever published a book on that subject before. Although he acknowledges previous works by Piero della Francesca, Albrecht Dürer, Sebastiano Serlio, and Federico Commandino, he believes all these authors “stopped on the doorstep” of the matter. In reality, Barbaro frequently plunged his hands into these sources, mentioning them explicitly just occasionally.

See Daniele Barbaro, La pratica della perspettiva (Venice: Camillo and Rutilio Borgominieri, 1569), pp. 34-35, copy preserved in Florence, Museo Galileo, MED 1973.

The book is subdivided in nine sections, or parti: the matter proceeds from the basic rules of linear perspective to the treatment of bi- and three-dimensional figures, from architecture and theatre set design to “secret” rules adopted by painters, from the planisphaerium to observations on lights, shadows and colours, from the measures of the human body to the instruments useful to draw perspectival views. The order of the sections and the scope of the work were the subject of several changes of mind and reconsiderations, and the result is a book featuring numerous evident scars. Some sections have been ruminated for decades, some others were put together in a hurry immediately before its publication.

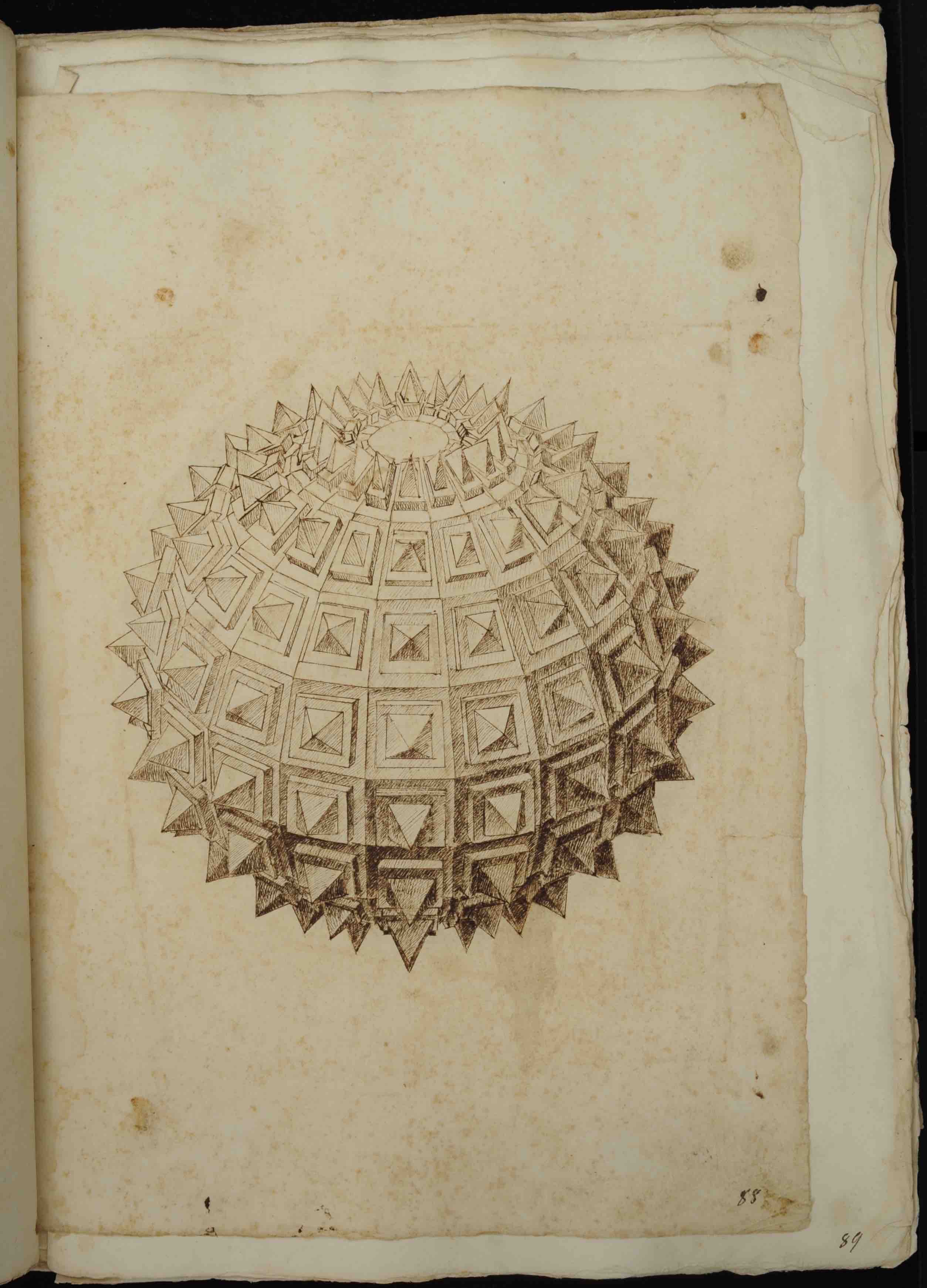

In the third section, Barbaro treats the geometric solids, and 3D forms in particular. Here he is frequently recurring to Dürer’s methods and explanations, adopting illustrative materials clearly derived from this source.

See Daniele Barbaro, La pratica della perspettiva (Venice: Camillo and Rutilio Borgominieri, 1569), pp. 48-49, copy preserved in Florence, Museo Galileo, MED 1973, with illustrations derived from Dürer.

The three surviving manuscripts which can be related to this publication, now preserved at the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, testify that Barbaro worked hard over the years to absorb in first person the techniques of this practice. These are the codices Lat. VIII, 41 (=3069), It. IV, 40 (=5447), and It. IV, 39 (=5446). They all present hundreds and hundreds of sketches and drawings (not always of excellent quality, to tell the truth). Barbaro identifies as his teacher during his early years Giovanni Zamberti, a recognised master in this field. The final publication bears just a selection of the schemes and drawings elaborated on these pages.

Some of the published woodcuts were recycled from earlier publications, and these appear more frequently in the second half of the book. Architectural details and examples have been taken not only from Barbaro’s former editions of Vitruvius, but also from Serlio’s books on architecture, which were recently re-published in Venice by Francesco Marcolini, a printer with whom Barbaro collaborated for the first edition of his Vitruvius.

See Daniele Barbaro, La pratica della perspettiva (Venice: Camillo and Rutilio Borgominieri, 1569), pp. 156-157, copy preserved in Florence, Museo Galileo, MED 1973, with woodcuts taken from Serlio.

The significance of La pratica della perspettiva, though, should not be underestimated: this was the first attempt to treat and condense the material into a logic sequence, and it inspired many other works on this subject, besides being one of the main sources of inspiration for Thinking 3D!

See more on the International Network Daniele Barbaro: In and Beyond the Text, co-ordinated by Dr Laura Moretti and funded by The Leverhulme Trust here.