By the second half of 16th century, a number of theoretical and technological innovations reshaped the architects’ practice: instrumental innovation fuelled by the printing, low-cost paper, and linear perspective development; diffusion and interpretation of Greek and Latin texts; surveys on ancient architecture; the “intellectual turn” invoked by Leon Battista Alberti. By adopting drawing as an extensive design tool, architects developed a number original visual tools for a synoptic control and presentation of design which begin to circulate by a wider audience.

Parallel to this, the use of models gradually decreased as their function was being replaced by drawings. Filippo Brunelleschi had discussed his design for the church of Santo Spirito in front of workers with only a plan in his hand. Donato Bramante presented only a half-plan of St Peter’s church to Julius II. Forty years later, in the Palazzo della Cancelleria, Giorgio Vasari depicts Paul III with a large plan of St Peter’s, eventually replacing the traditional donor’s model.

Around 1536, when Titian portrayed Giulio Romano showing a plan for a mysterious centric building and mimicking a compass with his fingers, in Rome, the Spanish bookseller Antonio Salamanca was collecting drawings and recovering the surviving coppers and models after the Sack of 1527.

Years before, Raphael had started a wide survey campaign on antiquities and monuments. In the famous letter written with Baldassarre Castiglione to the future Pope Leo X, he had also described the methodology and graphical procedures suitable for such a work, prescribing the use of plan, elevation and section, against the practice of scaenographia or perspective views. According to Vasari, he had also entrusted three engravers – Raimondi, Veneziano and Dente – with the reproduction of some of his drawings to be sold by Baviero dei Carrocci.

In introducing himself as an editor, Salamanca not only collected some of the circulating pictures but also produced new views of Rome. In particular, he asked the Tuscan architect and painter Domenico Giunti or Giuntalodi (1505-1560) for drawings of the two main Roman monuments: Pantheon and Colosseum.

While some of Northern artists (such as, for instance, Hieronymus Cock) used to enhance the ruined aspect of Colosseum, Giuntalodi proposed a composite reconstruction able to illustrate most of its feature as a building.

Giuntalodi, in particular, made a large perspective of the Colosseum in two sheets, no longer surviving but known via copies, which were engraved by Girolamo Fagiuoli and published by Salamanca in 1538. One sheet was showing half of the exterior elevation, up to the central span; the other combined ground plan – about 1/6 of the building was removed, possibly where the different curves of the oval plan construction fit – with sectional and interior elevations. As the perspective structure responded to the same vanishing point, the sheets could be assembled resulting in a single large view.

When Nicolas Béatrizet copied them for Antoine Lafréry, who became Salamanca’s partner from 1544 to 1577, he combined them into a single smaller picture. Salamanca and Lafrery inserted the picture in a sort of open collection named Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae, literally, the “Mirror of Roman Magnificence”. Tourists and collectors could look up a general list of hundreds of prints – at least 994 according to the University of Chicago collection –, choose their favourite ones and have them bound as a customized book.

The success of this view was endorsed by the number of its imitations; Ambrogio Brambilla copied it for Claudio and Francesco Duchetti, Lafrery’s heirs, in 1582 (and Matthijs Brill the Younger copied Brambilla’s drawing, too), and Giacomo Lauro reproduced it – quite roughly – in his Antiquae Urbis Splendore in 1612. Moreover, the view inspired Antoine Caron in 1566 for his famous Massacre under the Triumvirate, while Viviano Codazzi and Domenico Gargiulo translated it – and the Pantheon, too – into surprising paintings in late 1630s. Somehow, this view of the Colosseum, where almost 3/4 of the building is reconstructed and 1/4 is missing, became the official icon of the Colosseum, almost over-imposing onto the actual form of the monument.

Giuntalodi’s and Béatrizet’s drawings are important for a number of different topics, such as the problem of showing interior and exterior of a building at the same time, the use of symmetry axis as a graphic stratagem, the graphic solution for the section-cut and the public reception of artificial composite views.

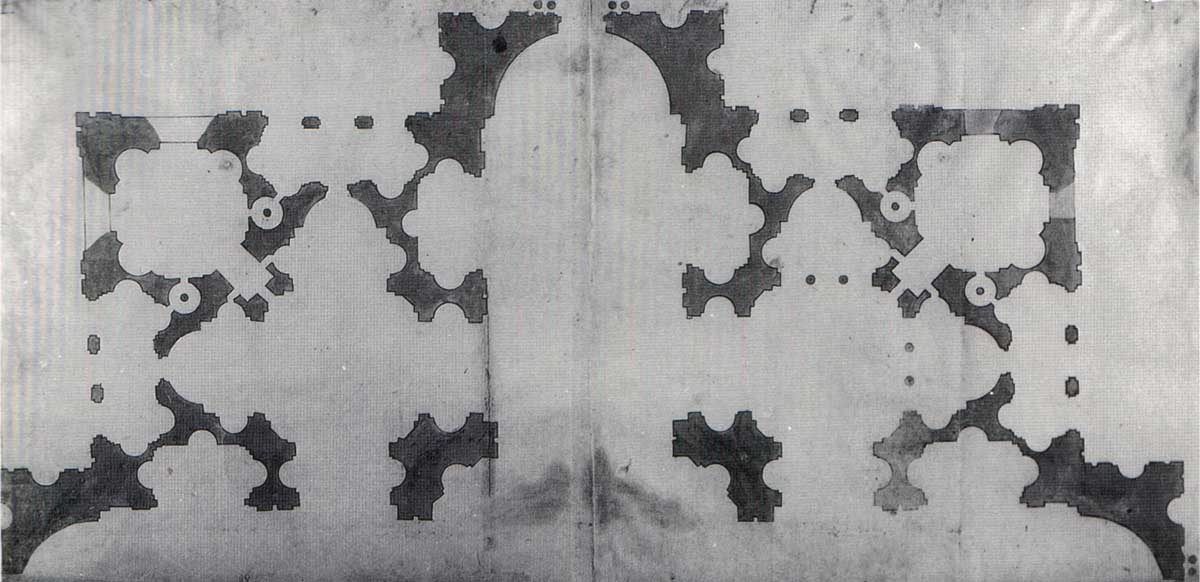

An instrumental use of the symmetry axis of buildings, already present in the 13th century notebook of Villard de Honnecourt, was developed in the last decade of the 16th century, when the treatise was then spread widely among designers, especially in Milan, Florence and Rome. Cutting a plan or an elevation along the axis of symmetry - but also a skull as shown by Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical sheets in Windsor - had turned out to be as a useful stratagem to save time and energy and to offer a both analytical and synthetic vision. It was used to take down notes quicker while traveling; to condense distant parts of the building into a single image; to compare design alternatives; to compare a measurable element in orthogonal projection with its perspective “sensible” version; and even to depict together ante and post operam.

These kinds of “artificial” drawings are something more than a direct, visual imitation of reality, being a sort of meta-designs which can be queried to extract spatial information about the building. Initially, they were destined to the architect himself and his circle. Progressively they were adopted for presentation, at least from 1500s onwards. After the Sack, Salamanca decided that tourists and collectors were as educated as to understand the conventional use of symmetry axis and able to eventually complete the missing parts. While Raphael’s prescriptions were intended to address architects and antiquarians’ approach to monuments, public’s gaze and attention were sensitive to pictorial works and light effects.

Baldassarre Peruzzi is likely to have shown Giuntalodi the pictorial opportunity of this kind of perspective drawings, as conjectured by Deswarte-Rosa, but the assignment of the idea of combining the interior and exterior of the Colosseum in a single perspective view is hard to establish. For example, similar sketches of both the Pantheon and Colosseum are in Damiano Pieti’s manuscript of the first vernacular, unfinished edition of Leon Battista Alberti’s treatise, which is dated 1538 and conserved in Reggio Emilia, while in the drawing Satirical Allegory: Mercury Purged, now at the Louvre and dated 1530-32, Peruzzi had drafted a quarter of an amphitheatre among the other antiquities in the background.

Anyway, Giuntalodi offers public a combination of painters’ and architects’ practice. While Giuntalodi’s view of the Pantheon still echoed Giuliano da Sangallo’s spaccati, whose picturesque rendering quality was largely inspired to the Roman landscape of ruins, his views of the Colosseum show a geometric rendering of the sectioned parts, like if they had been cut with a knife. Such an abstract solution, which seems to be coming directly from the designers’ practice of combining sections and projections together, was rejected by Beatrizet and other artists who copied Giuntalodi’s Colosseum. They gave the sectioned part rather the traditional effect of a ruined wall with blocks and bricks about to fall as the public was still supposed to appreciate more this kind to rendering than, for example, Antonio Labacco’s reconstructions of ancient temples.

The migration of graphical techniques from architects’ drawing board to the printers’ shop contributed to enhance the public’s reception and understanding of composite pictures and conventional images. In particular, the composition of different parts of building through an ambiguous use of the symmetry axis reveals the intent of a temporalization of the representation – as well the existence of an audience able to combine mental and visual information – and seems to suggest a literal interpretation of the term speculum.

St Paul’s celebrated phrase - Videmus nunc per speculum in aenigmate – is supposed to have contributed to the idea that the world is a God’s reflection, that reality is only an allegorical image men and women are called to decipher in order to interpret the divine will. The first encyclopaedias and moralistic treatises took the name speculum as it used to indicate a virtuous model of behaviour and knowledge to reflect in. Anyway, in the case of Roman engravings, the sense seems to become even more literal, an authentic two-dimensional representation of a three-dimensional reality. While the allegorical meaning of the term is partially evocated by the reconstructed Colosseum, an effective use of the “reflection” is here suggested.

Thus, in the context of the Speculum, a customizable collection of prints, the engraving of the Colosseum may result a sort of catoptric device that requires a mirror and human intervention to reveal the complete disegno of either the interior or exterior of the ancient amphitheatre. This sort of conjectural interactivity, which might have been inaugurated with the Bramantesque doubly symmetrical half-plan of St Peter’s, would have the consequence of compensate the observer’s difficulty in understanding the print and to make the architectural presentation a spectacular event, as well.

Further Reading

- Bury, M., The Print in Italy 1550-1620 (London, 2001).

- Carpo, M., Architecture in the Age of Printing: Orality, Writing, Typography, and Printed Images in the History of Architectural Theory (Cambridge, 2001).

- Colonnese, F., Carpiceci, M., “Between Antinomy and Symmetry. Architectural Drawings of Presentation and Comparison in the XVI Century,” in EGA 2018. Graphic Imprints, ed. by C. Marcos (Cham, 2018), 66-78.

- Deswarte-Rosa S., “Domenico Giuntalodi peintre de Martinho de Portugal à Rome”, Revue de l’Art 80, (1988): 52-60.

- Deswarte-Rosa, S., “Les gravures de monuments antiques d’Antonio Salamanca, à l’origine du ‘Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae’”, Annali di architettura 1, (1989), 47-62.

- Heuer, Ch., “Hieronymus Cock’s Aesthetic of Collapse”, Oxford Art Journal 32/3, (2009): 387-408.

- Martínez Mindeguía, F., “Anatomía de un dibujo: el Palacio de Caprarola, de Lemercier”, Annali di architettura 21 (2009): 115-25.

- Parshall, P., “Antonio Lafreri’s ‘Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae’”,” Print Quarterly 23/1 (2006): 3-28.

- Temple, N., “Plotting the centre: Bramante’s drawings for the new St. Peter’s Basilica”, in Recto Verso: Redefining the Sketchbook (Burlington, 2014), 65-82.

Online Resources

Antonio Lafreri’s Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae, http://speculum.lib.uchicago.edu.