When Napoleon Bonaparte sailed to Egypt in 1798, he not only brought with him military personnel, but also a group of French artists, scientists and scholars who would become the leading voices in a new field of study that emerged in the 19th century: Egyptology. Description de l'Égypte, published between 1809 and 1828 and consisting of ten volumes of text and fourteen volumes of plates, is the culmination of the careful documentation done by the members of Napoleon’s Egyptian expedition.

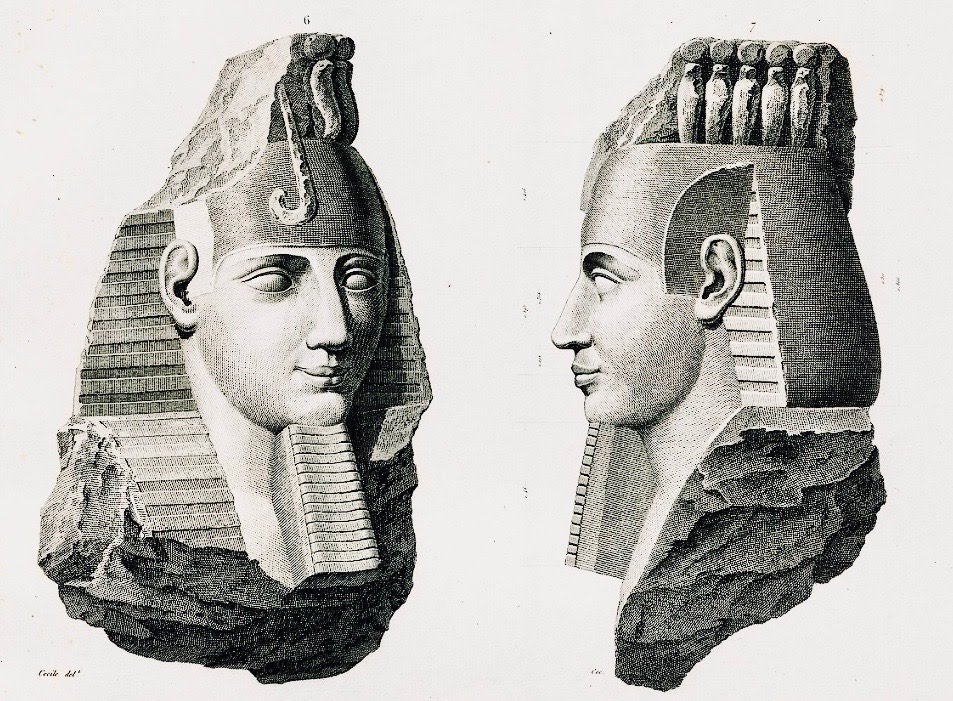

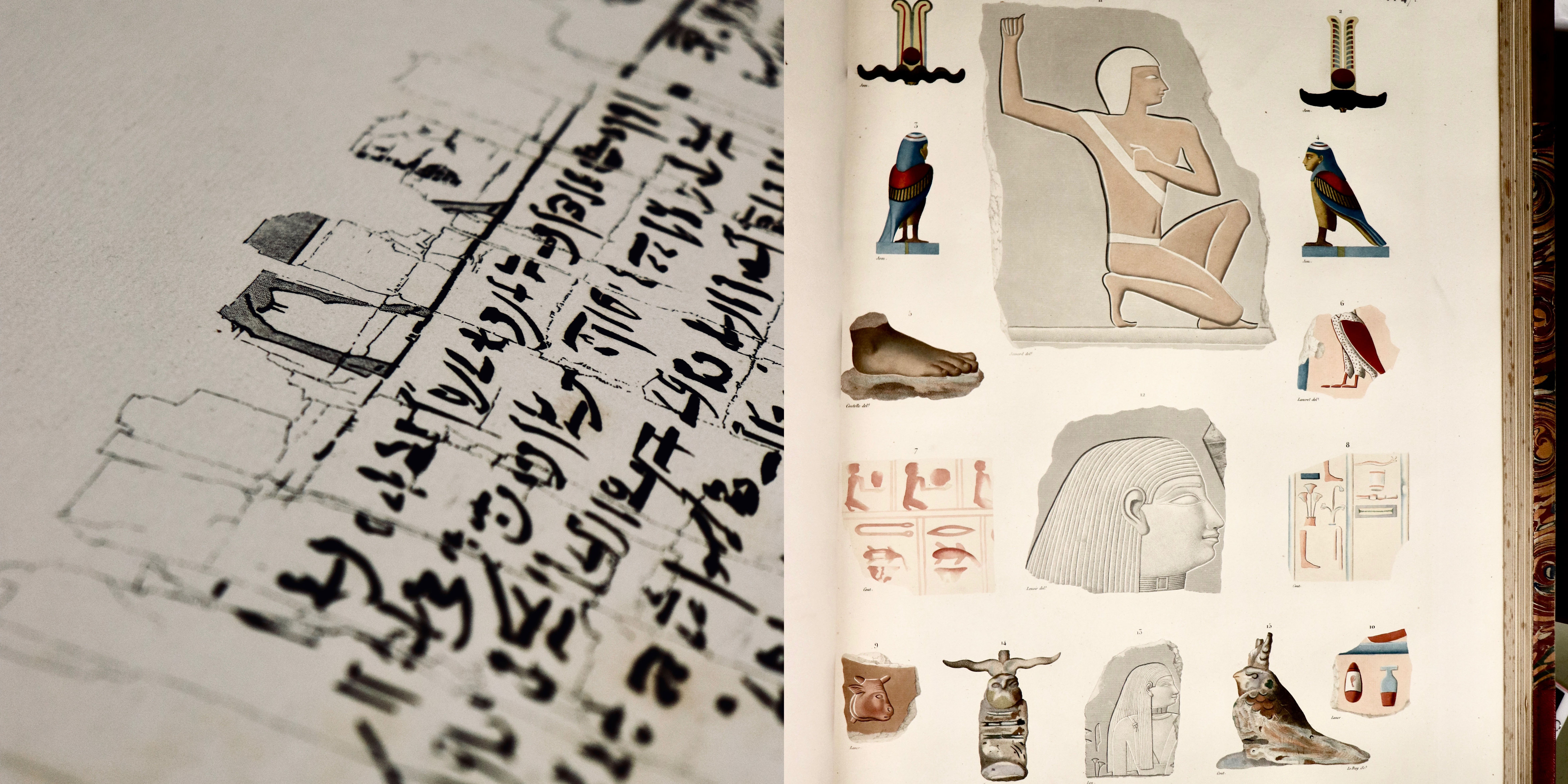

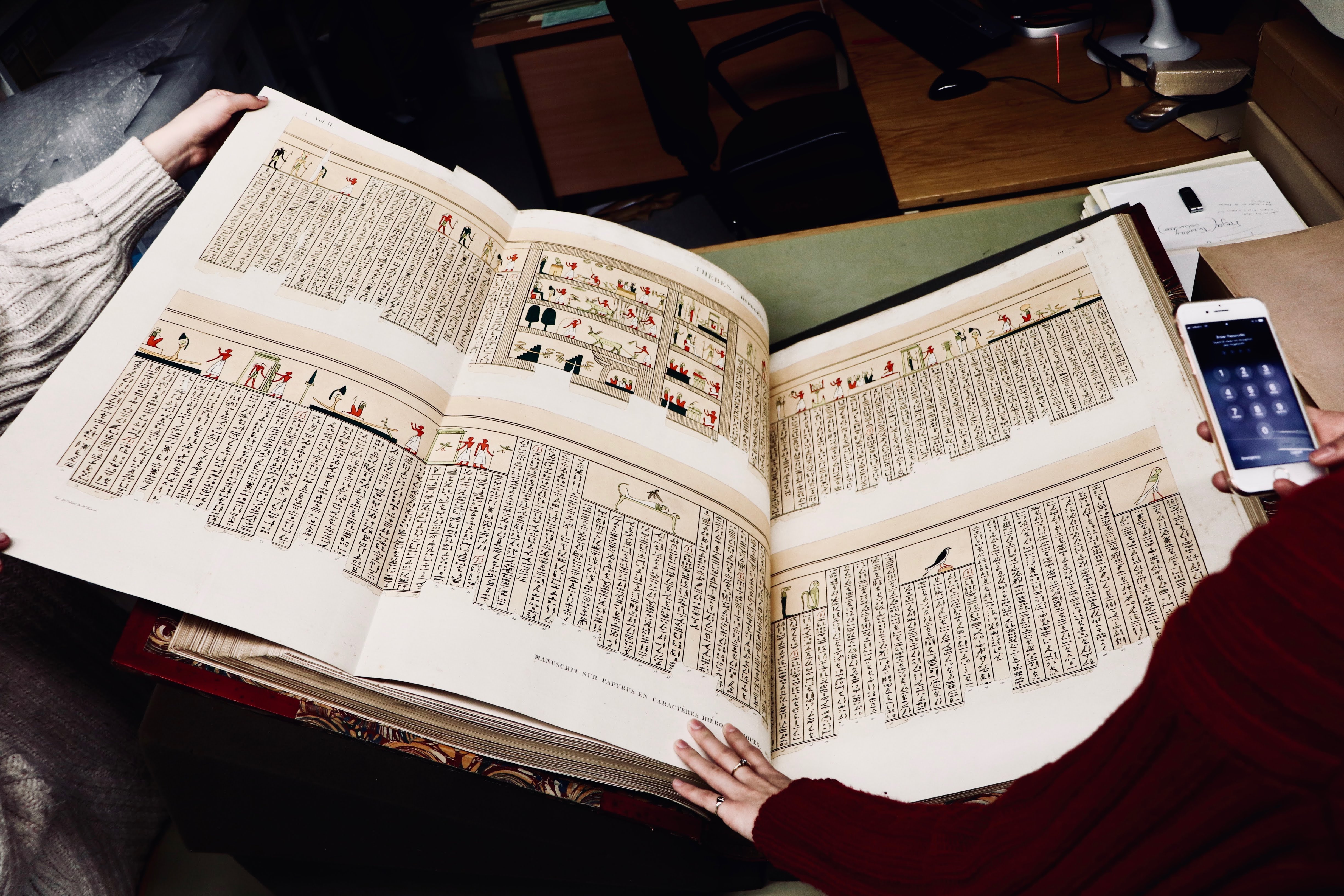

The volume considered is the second volume dealing with Antiquities, containing solely engravings and their descriptions mentioned in previous books. It focuses on Thebes and contains maps of the area, diagrams, and carefully documented artefacts and manuscripts.

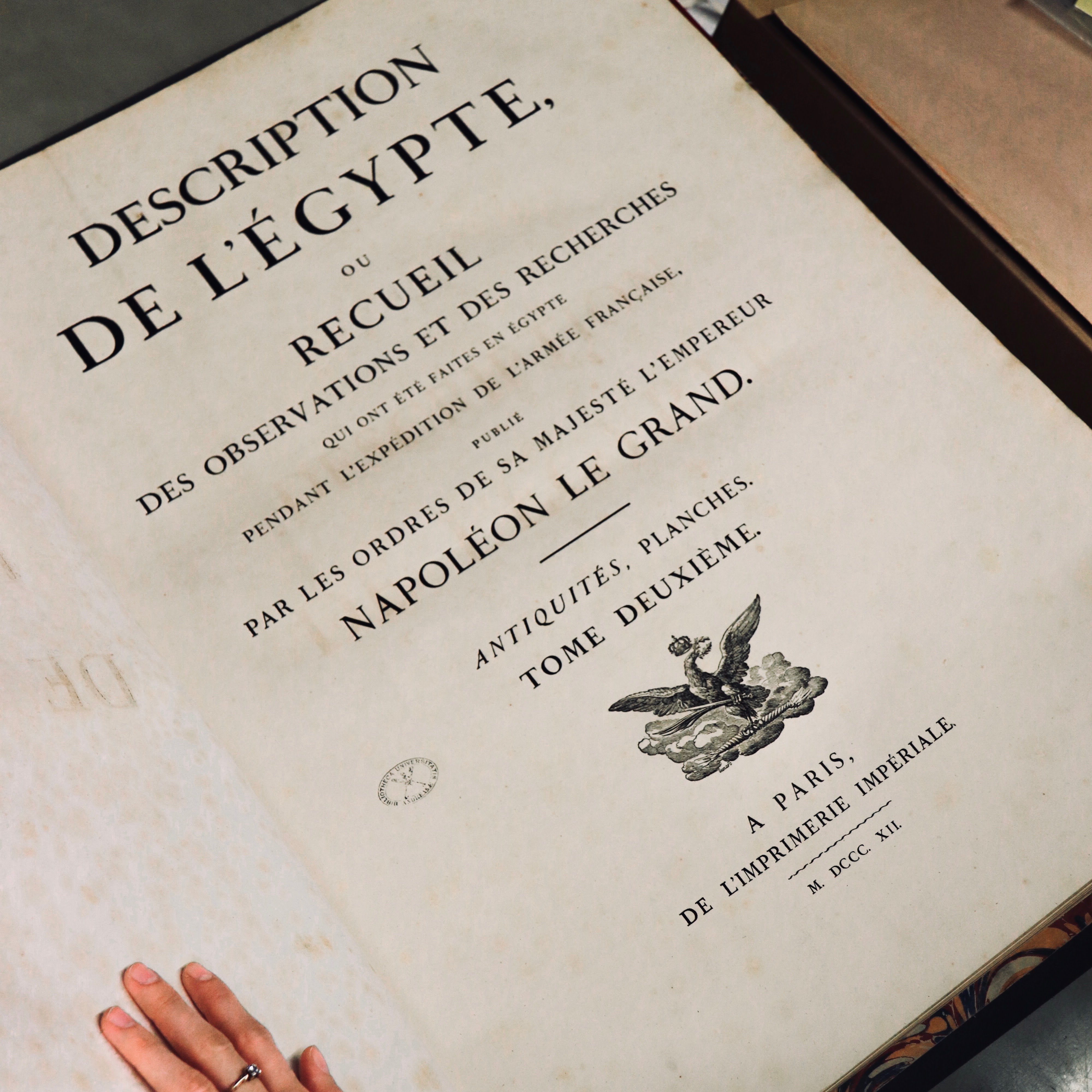

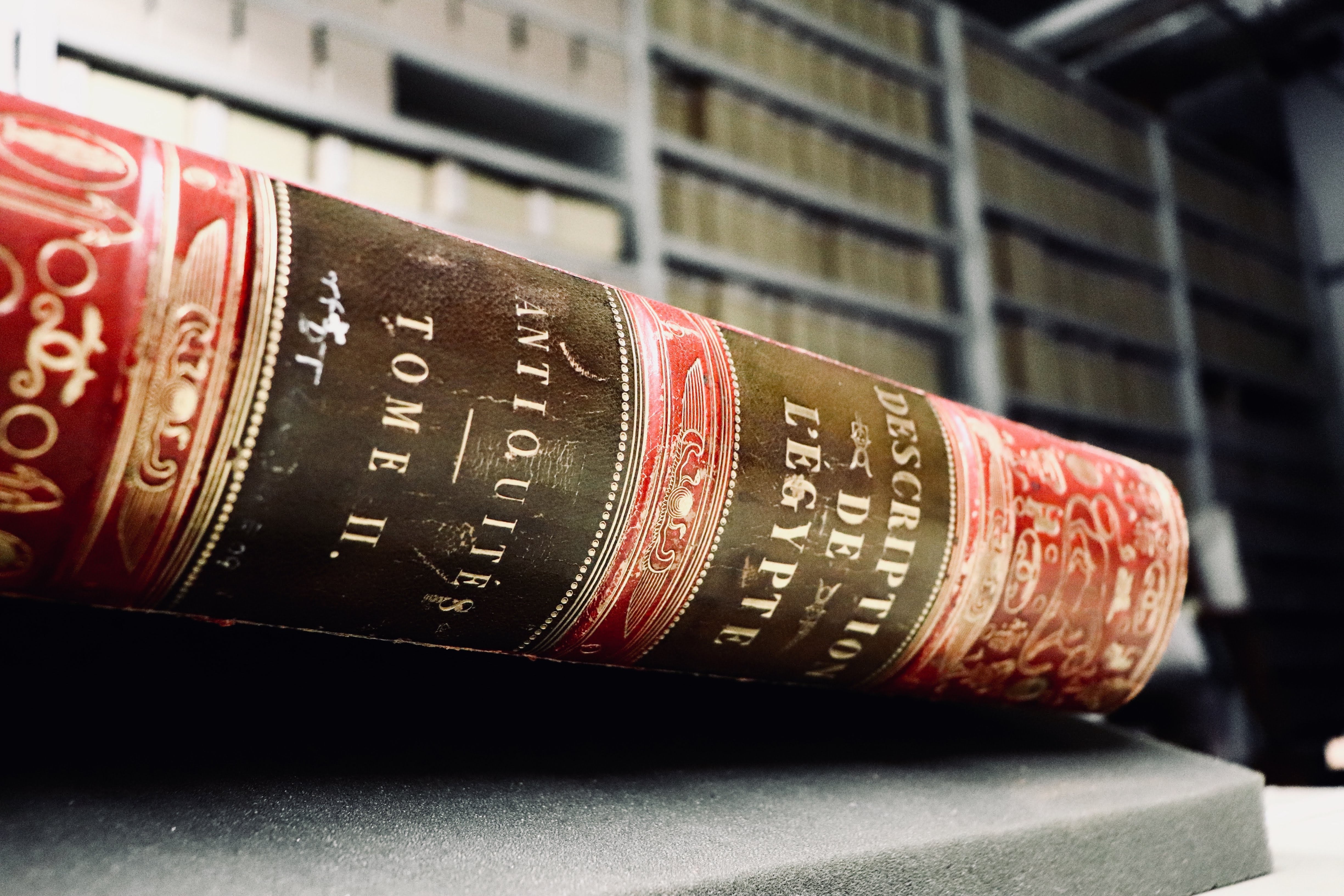

This particular volume of Description seems to belong to the first ‘Imperial’ edition, published by order of the emperor (“Napoleon le Grand”) under the supervision of Edme-François Jomard , who had the incredible task of compiling the works of 43 authors, transliterating Arabic words and even creating a special printing press for a work of this scale (successive editions were published simply by order of the King or the government). It follows an unusual folio format of 1m x 0.81cm, on vergé paper. The volume includes several fold out plates, which adds to the tactile and interactive nature of the book itself. Only 1,000 copies were printed, but it proved so popular that a second ‘Royal’ edition was published by the printing house of C. L. F. Panckoucke (Paris). A digitised version is available online.

At the time of its publication, Description was the most comprehensive record and inventory of Egypt’s lands and monuments and the largest printed work ever produced. Connected to the rise in the popularity of encyclopaedias, including Diderot’s Encyclopedie, many of the images are laid out in a scientific fashion. Fragments of parchment with hieroglyphics and sections of temple decoration are presented alongside anatomical representations of mummified remains. While this organization served to educate the population, in many ways, this project served as another way of asserting control of Egypt and rousing Imperialist support back in France.

The large-format illustrations of landscapes and monuments place the diagrams of antiquities in their context. This context, however, is not free from French intervention; the maps serve as a Western organization of foreign terrain and thus occupation of it, while coloured images of local figures appear whitewashed. Moreover, nearly all of the large illustrations include the small figures of French artists or scientists actively observing, exploring, and experiencing the landscapes that they have inserted themselves into.

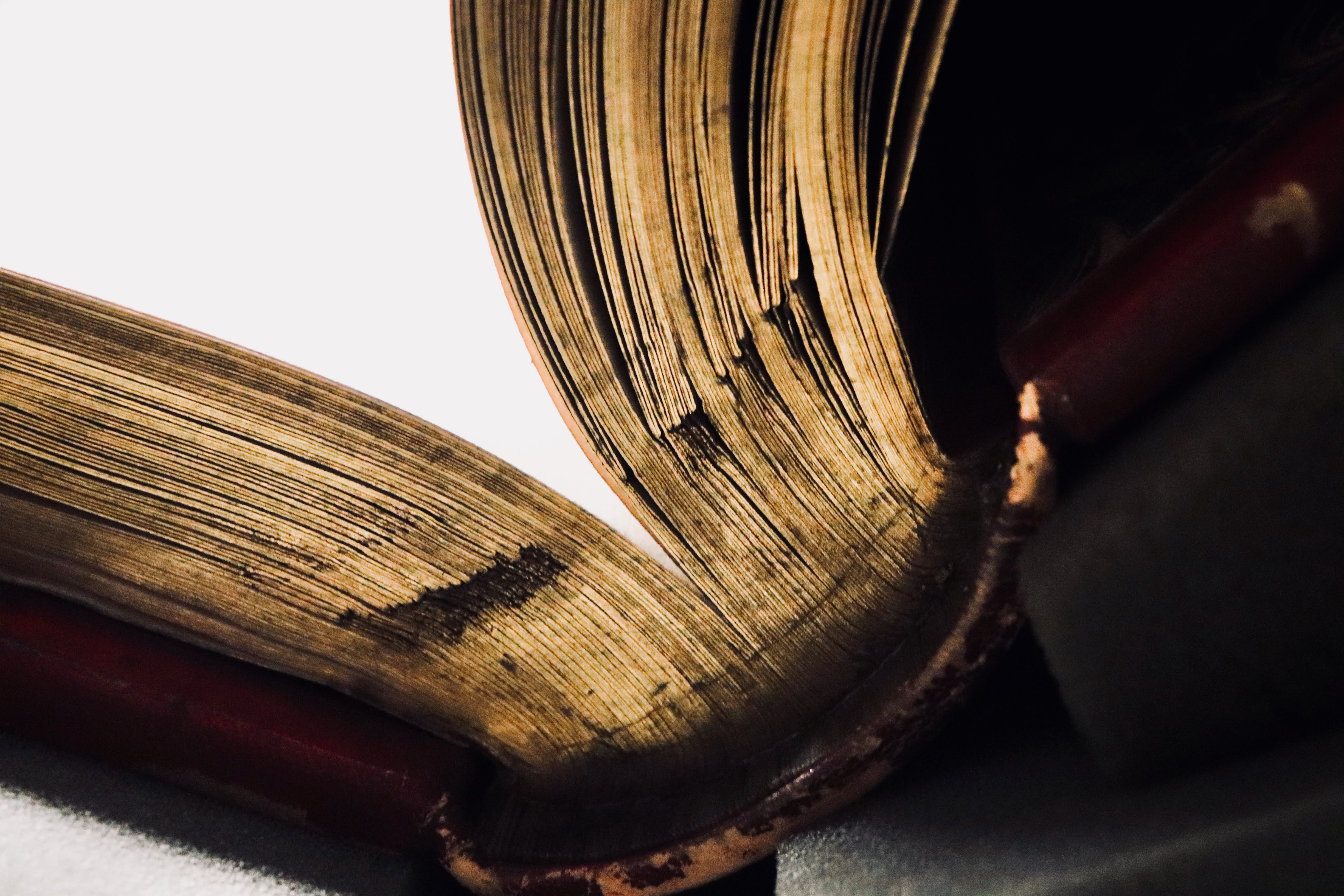

According to Edward Said in his seminal 1978 work Orientalism, “the Description de I’Égypte provided a scene or setting for Orientalism, since Egypt and subsequently the other Islamic lands were viewed as the live province, the laboratory, the theatre of effective Western knowledge about the Orient” (42-43). The encyclopaedic diagrams throughout Description remove objects from their home in Egypt and suspend them against the stark white pages of the Encyclopaedia, whereby the objects lose their meaning as cultural and religious objects and become, in the eyes of the 19th century French viewer, objects of scientific study owned by the French. The precise truth-to-nature style creates a “reality effect” throughout the book, from the illustrations of the tattered edges of the ancient manuscripts to the hieroglyphics and Egyptian symbols that decorate the binding of the heavy tome.

The volume pictured here is owned by the University of St Andrews and is in excellent condition; while some of the pages have yellowed specks and folds, the gold gilt on the edges of the pages is intact and completely uncreased. The binding shows very few signs of wear, indicating minimal or incredibly cautious usage.

The Imperial Edition reflects perfectly what Napoleon was trying to achieve; the richness of its materials, the gold gilding, the colour plates that were expensive to produce and simply its colossal size, scream about the megalomaniac tendencies of the General who desperately clung on to his victories and attempted to covered up his failures in the East.

Description’s influence was enormous; it established Egyptology as an intellectual discipline, it gave rise to the craze of Orientalism of Delacroix and Gautier, while its engravings contributed to Champollion’s deciphering of hieroglyphics. Furthermore, according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, it had a profound effect on the decorative and architectural styles of France during the 1810s and 20s. The legacy of the Orientalist style can be seen in the 19th century French conquest of North Africa, and the subsequent violence that has consequented from French colonialism as a whole.

Nicole Slyusareva, Julia Westerman, Emily Wolstenholme-Rimmer

Further Reading

Bednarski, Andrews, Holding Egypt. Tracing the Reception of the Description de l'Égypte in Nineteenth-Century Great Britain. London, Golden House Publications, 2005. ISBN 0-9550256-0-5. For an understanding of the reception of the book in the UK.

Anne Godlewska, “Map, Text and Image. The Mentality of Enlightened Conquerors: A New Look at the Description de l’Égypte,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, vol. 20, No. 1 (1995), pp. 5-28. www.jstor.org/stable/622722.

William H. Peck, “Description de l’Égypte, A Major Acquisition from the Napoleonic Age,” Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts, vol. 51, No. 4 (1972), pp. 112-121. www.jstor.org/stable/41504521.

---

Fully digitised copy of this volume can be found here.

Older books on Egyptology include John Greaves's Pyramidographia (1646), and Frederic Louis Norden’s Voyage d'Egypte et de Nubie (1755).