In the nineteenth century, the boundaries between illusion and reality became increasingly blurred, as scientists and artists began to test the limits of human perception with unprecedented enthusiasm. Optical toys such as kaleidoscopes, thaumatropes, stereoscopes and zoetropes achieved great popularity amongst the public as objects suitable for personal amusement, but in reality they set out to manipulate time and space and experiment with vision in ways never before attempted, which is why they also came to be known as ‘philosophical’ toys.

In a pre-cinematic era, many of these toys aimed at recreating the illusion of motion through bi-dimensional supports like paper and cardboard – such is the case, for instance, of flip (or flicker) books and phenakistiscopes, both early animation devices which allowed to transform a rapid succession of images into a single, moving one. However, a number of optical toys were specifically developed to cast the illusion of three-dimensionality as well. Stereoscopes, anaglyphs and megalethoscopes are but a few examples of a series of technical devices able to produce surprisingly modern 3D images, to the bemusement and wonder of the general public. After all, at least since Leonardo da Vinci conceived the first known example of anamorphic drawing in the fifteenth century, three-dimensionality has been chased and dreamt of like a chimerical creature by both artists and science men, prompting some of the most ingenious creations of the human mind.

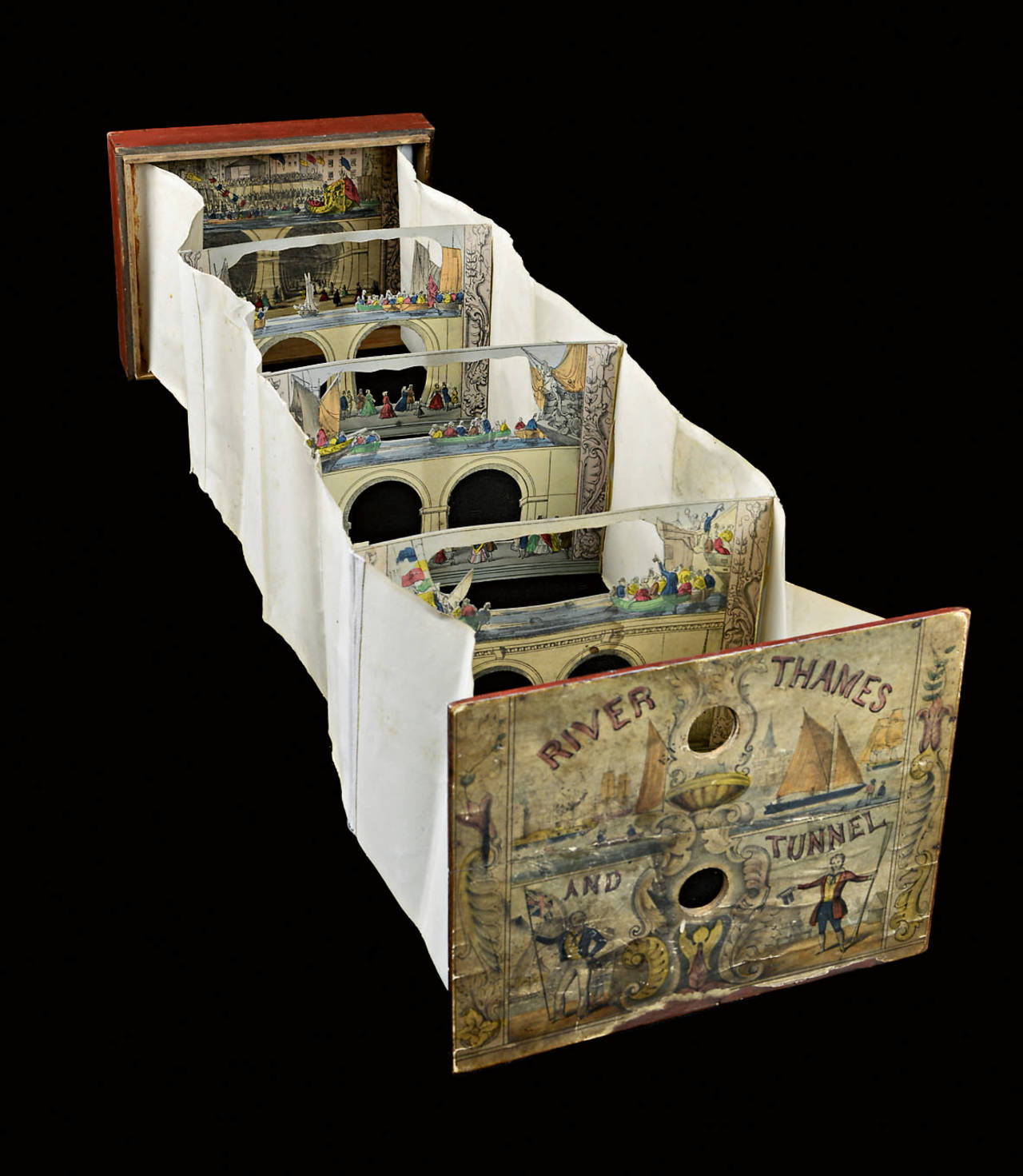

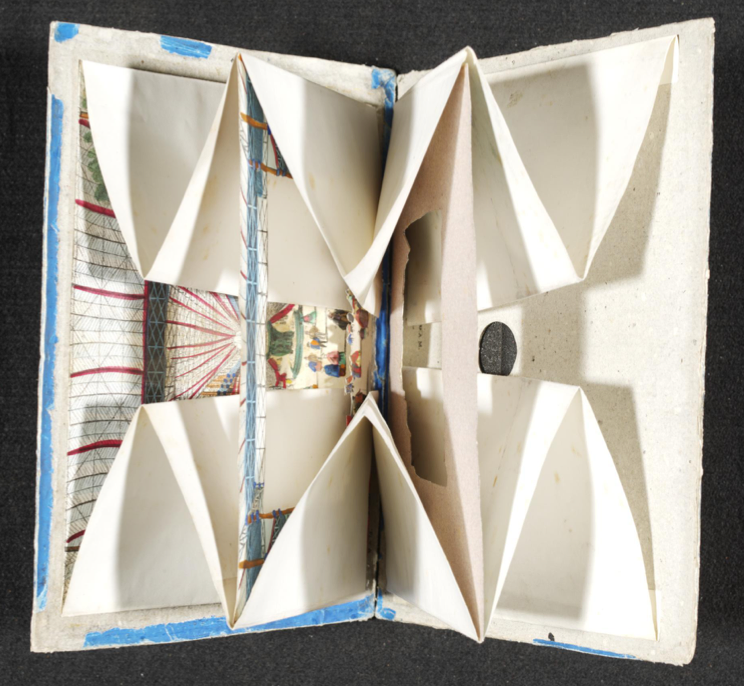

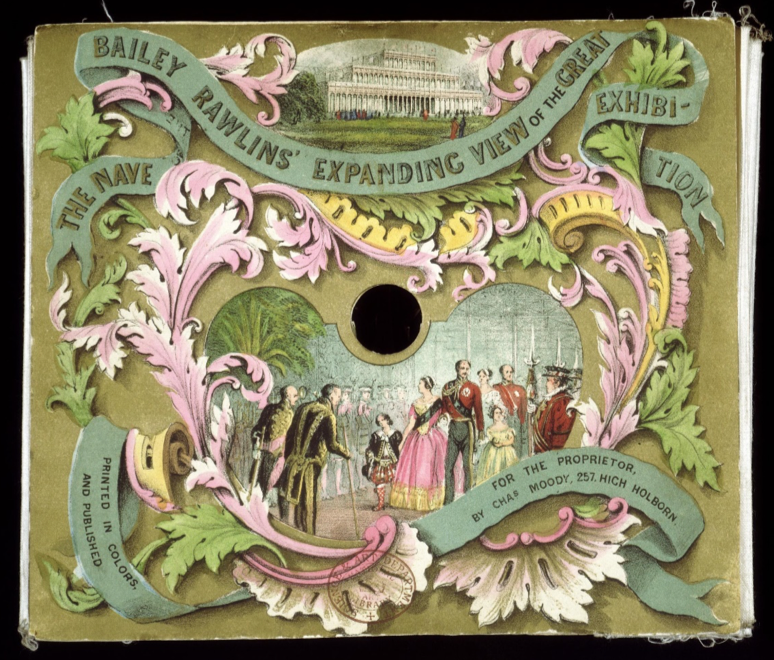

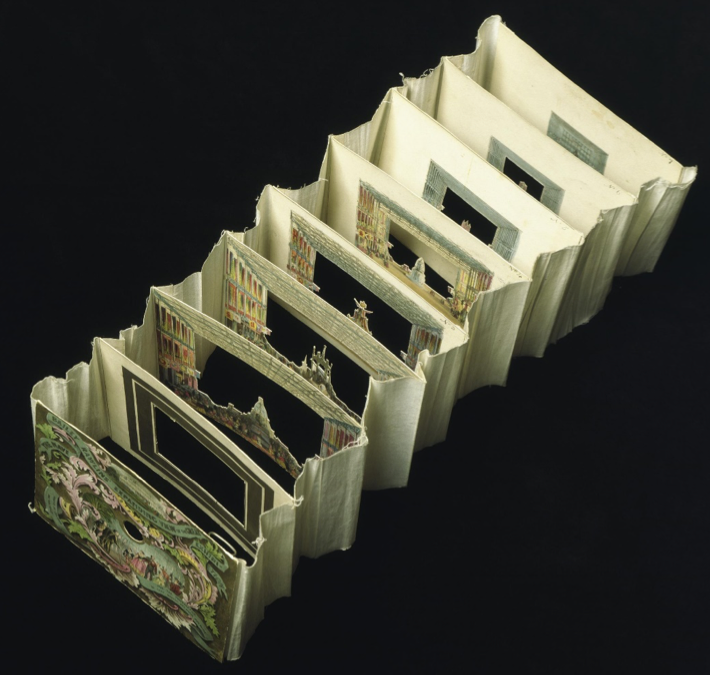

Amongst such a profusion of optical devices, some that certainly deserve to be mentioned are paper peep shows, also called ‘tunnel books’. Although different kinds of peep shows had been widely circulating in Europe since the fifteenth century, when the Italian humanist Leon Battista Alberti allegedly invented the earliest known specimen, it is in the 1800s that tunnel books saw the light as optical toys and entertaining devices. As the name suggests, they were conceived as a succession – a tunnel – of layered images on paper, bound together and viewable through a tiny hole open on the front cover. Long before the advent of 3D cinema and virtual reality, these portable dioramas – which could be expanded more or less like an accordion – allowed 19th-century audiences a glimpse into other worlds, often remote in time and space, and rich in wonderous details.

Colourful exotic landscapes, sumptuous palace interiors, majestic processions and breathtaking panoramas magically unfolded beyond the eyes of the viewers, who could also immerse themselves in faithful recreations of historical events, like the opening of the Thames Tunnel or Napoleon’s invasion of Moscow in 1812. Some of the most interesting specimens are kept in the V&A in London, home to the largest collection of paper peep shows in the world: not only do they differ in terms of contents and decorative technique (ranging from coloured lithography, to engraving, etching and aquatint), but they also come in a variety of sizes, with a few nearly reaching two metres long when fully extended.

Amazing examples of ‘3D thinking’ before the digital revolution, these 19th-century pocket-size tunnel books powerfully illustrate, once again, how the bi-dimensional properties of paper came to be exploited in creative ways, to support phantasies and endeavours of the human genius.

More images available on the V&A website.